Transferrin Saturation, Dietary Iron Intake, and Risk of Cancer

Arch G. Mainous III, PhD; James M. Gill, MD, MPH; Charles J. Everett, PhD

Ann Fam Med. 5; 3 (2): 131-137. ©5 Annals of Family Medicine, Inc.

AbstractPurpose: Transferrin saturation of more than 60% has been identified as a cancer risk factor. It is unclear whether dietary iron intake increases the risk of cancer among individuals with transferrin saturation of less than 60%. The purpose of this study was to examine the association of dietary iron intake and the risk of cancer among adults with increased transferrin saturation.

Methods: Analysis of a cohort study, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, was performed. US adults (aged 25 to 74 years at baseline) were followed up from baseline in 1971-1974 to 1992 (N = 6,309).

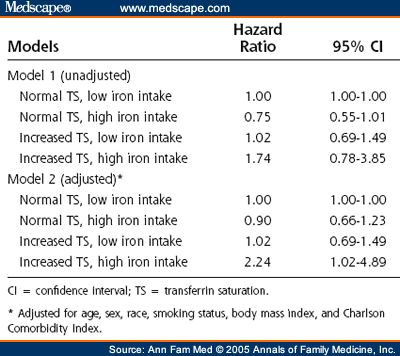

Results: A total of 7.3% of the US population had a serum transferrin saturation of more than 45% at baseline. Intake of dietary iron was essentially uncorrelated with transferrin saturation ( r = 0.04). Compared with individuals who had normal serum transferrin saturation and low dietary iron intake, individuals whose serum transferrin saturation was more than 45% and who had high dietary iron intake also had an increased adjusted relative risk of cancer (2.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-4.89). Increased risk was not found for individuals with a transferrin saturation of more than 45% but a normal dietary iron intake (hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.69-1.49). Transferrin saturation levels could be set as low as 41%, and the individuals with high transferrin saturation and high dietary iron intake would still have an increased adjusted relative risk of cancer (hazard ratio, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.04-3.82).

Conclusions: Among persons with increased transferrin saturation, a daily intake of dietary iron more than 18 mg is associated with an increased risk of cancer. Future research might focus on the benefits of dietary changes in those individuals with increased serum transferrin saturation.

Introduction

Recent evidence has suggested that increased body iron stores, as indicated by high percentages of transferrin saturation, may be associated with an increased risk for mortality. In cohort studies, increased transferrin saturation is associated with an increased all-cause mortality risk, even after controlling for common mortality risk factors.[1,2] The mortality risk associated with increased transferrin saturation is higher when those with increased transferrin saturation have an additional attribute that may interact with iron stores to potentially increase oxidative stress.[3,4] For example, persons with increased transferrin saturation who consume high levels of dietary iron or red meat have an increased mortality risk, whereas the risk is not increased for persons with high transferrin saturation but a normal dietary intake of iron or red meat.[2]

In addition to an increased all-cause mortality risk with increased transferrin saturation, research has shown a weak positive association between the percentage of transferrin saturation and the risk of cancer.[5,6] In one study in the United States, a significant trend was found for the risk of cancer among men that increased with each successive quartile of transferrin saturation.[5] The highest quartile of transferrin saturation (transferrin saturation levels of > 37%) did not have a significantly higher relative risk than the lowest quartile, however. Among both men and women, the risk of cancer was not significant until the transferrin saturation was at least 60%.[7]

In another study from Finland, the relative risk of cancer did not vary significantly between quartiles of transferrin saturation.[6] Persons with a transferrin saturation level of 60%, which corresponded to the 97th percentile, however, had a significantly increased risk of any type of cancer, as well as colorectal cancer.

The data relating transferrin saturation to cancer risk suggest that high levels of transferrin saturation, consistent with a predisposition to iron overload, increase a person´s risk.[8] It is unclear whether the cancer risk associated with elevated transferrin saturation is increased by consumption of high levels of dietary iron in the same manner as the association with mortality. Moreover, few data exist to indicate whether consumption of high amounts of dietary iron among persons with lower transferrin saturation carries an increased cancer risk. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine, in a nationally representative cohort, the risk of cancer among persons with increased transferrin saturation who consumed high levels of dietary iron.

Methods

This cohort study followed up persons aged 25 to 74 years at the time of the index interview in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) I (1971-1974). The NHANES I baseline data were merged with the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study (NHEFS) data (1982-1984, 1986, 1987, and 1992).

NHANES I was designed to collect extensive demographic, medical history, nutritional, clinical, and laboratory data representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian US population. The survey was a multistage, stratified probability sample of clusters of persons aged 1 to 74 years. It was conducted from 1971 to 1975. The NHANES I survey design included oversampling of certain population subgroups, including persons living in poverty areas, women of childbearing age (aged 25-44 years), and elderly persons (aged 65 years and older).

The NHEFS is a national longitudinal data set that allows investigation of the relationships among clinical, nutritional, and behavioral factors assessed at baseline NHANES I and subsequent morbidity, mortality, and institutionalization. The NHEFS initial population includes the 14,407 participants who were aged 25 to 74 years when first examined in NHANES I. More than 98% of the participants in the initial NHANES I cohort were traced and supplied data in the 1992 NHEFS.

The follow-up information was gathered in 1 of 3 ways. Study participants interviewed were those who could be contacted and could participate. Surviving participants were always administered the subject questionnaire. If the original participant was alive but incapacitated, a slightly modified version of the subject questionnaire was administered to a proxy respondent. A separate proxy questionnaire was used only when the participant had died. Finally, for participants who had died between the NHANES I index interview and the follow-up interview, information from death certificates was recorded.

A total of 1,681 proxy respondents were interviewed in the 1992 NHEFS. Of these, 551 responded for an incapacitated participant and were administered a modified version of the subject questionnaire, and 1,130 responded for a deceased participant and thus were administered the proxy questionnaire.

The total number of persons with recorded transferrin saturation, dietary iron intake, smoking status, and complete follow-up data was 7,772. For this study, we excluded participants who had previous physician-diagnosed malignant tumors before the NHANES I examination (n = 91). In an effort to provide the most stable estimate of intake of dietary iron, we also excluded individuals who reported that the 24-hour dietary history did not represent the way that they usually eat (n = 1,372). These exclusions resulted in an unweighted cohort of 6,309 persons. This unweighted cohort was weighted and the design effect controlled for so that the population used for all analyses in this report represented the US adult noninstitutionalized population at the baseline of 62,720,183 persons.

Transferrin Saturation

In the original NHANES I, serum transferrin saturation was measured. The percentage of serum transferrin saturation was calculated by National Center for Health Statistics personnel by dividing the serum iron level by the total iron-binding capacity. We defined increased serum transferrin saturation at several levels based both on the literature and on our investigation of how low transferrin saturation might be in the presence of high dietary iron intake to still yield an increased cancer risk.[9] The first cutoff value of more than 45% had previously been proposed or used in population-based studies as one of the lowest levels of serum transferrin saturation that might be considered increased.[10,11] This level is substantially lower than a transferrin saturation of 60%, or 1.1% of the adult population, found previously to be associated with the risk of cancer without knowledge of dietary iron intake.[6,7] In addition to the 45% cutoff, we also investigated transferrin saturation levels at levels less than 45% to see whether these levels (which are not normally considered elevated) carried an increased risk in the presence of high dietary iron intake. Compared with persons at the 60% level, persons at these lower levels of transferrin saturation represent a much larger population at potentially increased risk.

Iron Ingestion

Iron ingestion was measured by using the 24-hour dietary recall found in the NHANES I. Total iron intake (milligrams per day) was estimated by the National Center for Health Statistics for this 24-hour period. The US recommended daily allowance for daily iron intake is 8 mg for postmenopausal women, 8 mg for all men, and 18 mg for premenopausal women.[12] Previous studies calculated a potential risk from excessive iron intake of 25 to 50 mg of iron per day.[12,13] For this study, more than 18 mg of iron per day was considered “high intake.”

Cancer Events

Incidents of cancer included reports of both diagnosis and mortality and were determined by answers to interview questions in the 1982-1984, 1986, 1987, and 1992 NHEFS interviews. The date for diagnosis of cancer was reported in the interviews. Information from death certificates was used only in cases in which the occurrence of cancer had never been reported during an NHEFS interview. Thus, because no other date was reported for the individual, the time at death was used for the cancer event. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes associated with cancer mortality were 140 through 239. Nonmelanoma skin cancer ( International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision , code 173.XX) was not classified as a cancer event.

Control Variables

We examined the independent relationship of increased serum transferrin saturation and dietary iron intake to cancer events by controlling for potential confounders. Control variables that were available in the NHANES I baseline were age, sex, and race. Four age categories were defined (25-34, 35-52, 53-69, and > 69 years). Race followed the NHANES I designations (white, black, and other). Because of our focus on cancer events, we also included body mass index (BMI) and self-reported smoking status (ever- or never-smokers) at baseline or during the 1982-1984 interview. BMI was calculated from measured height and weight information, and values more than 30 kg/m2 defined obesity.

In an effort to control for severity of illness, we included comorbidity conditions. A variety of conditions were assessed in NHANES I. Comorbidities were positive responses in the baseline interview to questions regarding whether a doctor ever told the patient that he or she had 1 of 40 different conditions. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated from the responses to these questions.[14]

Data Analysis

We classified the population into 4 groups based on normal and increased transferrin saturation and low and high iron intake. For analysis of the NHEFS, we used sampling weights to calculate prevalence estimates for the civilian noninstitutionalized US population. Because of the complex sampling design of the survey, we performed all analyses with SUDAAN (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC). Thus, the population used in the analysis represented more than 62 million people. In an effort to control for potential misclassification of persons as being cancer-free at baseline who actually had cancer but had not been diagnosed, we left the analysis censored to exclude any cancer event for the first 3 years of the cohort.

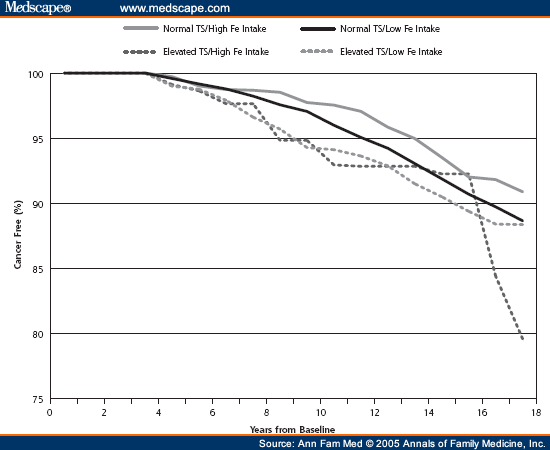

Using the population estimates generated by SUDAAN, we graphically show the cumulative percentage of cancer incidence as the unadjusted relationship between cancer events and normal or increased serum transferrin saturation and low or high iron ingestion. We performed Cox proportional hazards analysis with cancer event time for each group, controlling for age, sex, race, smoking status, BMI, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Although we believed that the interaction between transferrin saturation and dietary iron intake was based on having high levels of each, thus necessitating the categories used in the dummy variable listed previously, we also computed a model that investigated a statistical interaction between the 2 variables when they were both coded as continuous variables. In these models, cancer-free survival time was a continuous variable measured in 1-year increments up to 18 years from baseline. We evaluated the proportionality of the hazards through examination of the Schoenfeld residuals.[15]

Results

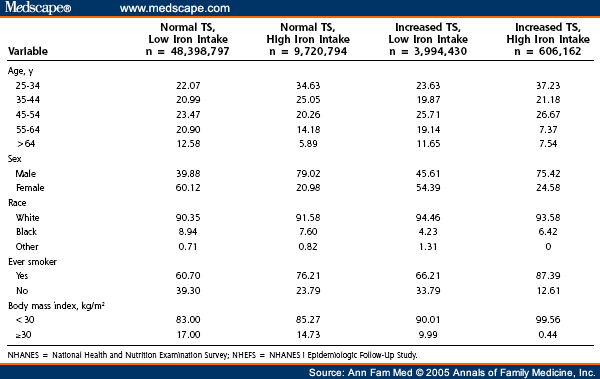

A total of 7.3% of the adult US population aged 25 to 74 years at baseline had serum transferrin saturations of more than 45%, and 16.5% of the adult population had iron ingestion of more than 18 mg/d. Serum transferrin saturation percentages and dietary iron intake had a weak Pearson correlation ( r = 0.04). Only 1.0% of the adult population had both increased serum transferrin saturation and high iron ingestion ( Table 1 ). Overall, 12.0% of the adult US population developed cancer between 4 and 18 years after the baseline examination.

The unadjusted relationships between cancer events, serum transferrin saturation more than 45%, and dietary iron intake are presented in Figure 1. Without adjustments, the Cox proportional hazards model analysis indicates that increased serum transferrin saturation did not significantly increase cancer risk ( Table 2 ). After adjustment for age, sex, race, smoking, BMI, and comorbidities at baseline, however, the group with increased serum transferrin saturation and high dietary iron intake had a relative risk of cancer (hazard ratio [HR]) 2.24 times more than that of the group with normal serum transferrin saturation and low dietary iron intake. The results of the Schoenfeld analysis indicated that the hazards were proportional. No significant interaction was found in the adjusted analyses by including transferrin saturation and dietary iron as continuous variables (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 1.00-1.00) rather than categorizing them as low and high on the basis of previous clinically specified levels.

Figure 1. Population percentage cancer-free for normal vs elevated transferrin saturation (TS)> 45% and low vs high iron (Fe) intake.

When we examined dietary iron intake and the risk of cancer at varying levels of transferrin saturation, we found in adjusted models that for transferrin saturation of 40% and dietary iron intake of 18 mg/d, the risk of cancer was not significant (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 0.83-3.06). A significant risk, however, was found at transferrin saturation levels of more than 41% (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.04-3.82), and a transferrin saturation of more than 43% yielded the highest risk of cancer when dietary iron was more than 18 mg/d (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.21-4.42). At more than 50% transferrin saturation, the sample in the high transferrin saturation and high dietary iron group becomes too small to make reliable population estimates.

Discussion

This study shows that in a national cohort of persons with increased transferrin saturation, a higher iron intake is associated with an increased risk of cancer and cancer mortality. This finding held true after controlling for demographic differences, such as age, sex, and race, as well as for differences in health status and comorbidities. What was particularly striking was that increased transferrin saturation was associated with a higher cancer risk only when it was combined with a high iron intake. Persons with a normal iron intake did not have higher cancer rates, even when their transferrin saturation level was high. Moreover, the results indicate that transferrin saturation in the presence of high dietary iron intake carries an increased cancer risk even at levels lower than what have previously been considered to be increased transferrin saturation. These results corroborate the results of a previous study that examined the combined effect of iron intake and transferrin saturation on overall mortality.[2] In that study, high iron intake and increased serum transferrin saturation were associated with higher mortality rates; however, as with the present study, the higher risk was found only when these 2 risk factors occurred in combination.

The results of this study may also help to explain the conflicting results of previous studies regarding transferrin saturation and cancer risk. Previous studies have suggested a weak positive association between transferrin saturation levels and the risk of cancer; significant independent risk appeared only at high levels of transferrin saturation (> 60%).[5â€â€7] By focusing on the influence of the ingestion of dietary iron on the risk of cancer among persons with increased transferrin saturation, this study elucidates the risk of cancer associated with increased transferrin saturation. It could be that these previous studies found few and inconsistent results mainly because they examined transferrin saturation without also considering iron intake. Because most people have a low iron intake, the association between iron stores and the risk of cancer is diminished when an undifferentiated population is examined without accounting for iron intake. By stratifying by iron intake, as in this study, the effect of combined iron intake and transferrin saturation indicates a relationship that is obscured when transferrin saturation is examined without accounting for iron intake.

These results have much broader implications than studies that have focused on the risk of cancer among persons with hereditary hemochromatosis, a condition that exhibits iron overload.[16â€â€19] Some studies investigating hemochromatosis have found an increased risk of cancer. A focus on a genetic marker for hemochromatosis as a risk indicator would seem to be too restrictive, because the prevalence of the C282Y mutation of the hemochromatosis gene is estimated at 1 in 200 in countries with a predominantly northern European origin.[20] The present results suggest that more than 7% of US adults are at risk for cancer if they consume high levels of dietary iron.

Although we can only speculate here on a potential clinical profile of persons with high transferrin saturation and high dietary iron intake, some comments might still be useful. Persons in this at-risk group were more likely to be smokers and to not be obese. Smoking and obesity have both been linked to the risk of cancer development: smoking carries an increased risk, and normal weight has a lower risk than obesity.[21,22] These characteristics may have contributed to the lack of a significant unadjusted relationship between transferrin saturation and dietary iron and cancer. When both of these variables were controlled for in the analysis, however, the transferrin saturation – dietary iron variable was significant.

Limitations of the study include the use of a 24-hour dietary history to assess iron intake. Assessment of the exposure for total dietary iron was made only once and by recall rather than objective measurement. We have no information on dietary patterns after the baseline. Even so, we attempted to obtain a stable dietary measure by excluding those who indicated that their diet in the past 24 hours was not indicative of their usual diet. Other studies have shown that middle-aged people are likely to have a stable nutrient intake for many years.[23,24] A second limitation of the study is the ascertainment of the outcome variableâ€â€in this case, cancer. The measure of a cancer event was mixed between information on death certificates and family or self-report. Differences in the source of information may have decreased the reliability and validity of the combined measure. A third limitation of this study is that although it is a longitudinal cohort design, it measures associations between variables and does not assess causality. A fourth limitation of the analysis is that we were limited by the number of individuals with high transferrin saturation and high dietary iron in whom cancer developed. Thus, although we could examine the general relationship, we were unable to examine on a population level the specific types of cancer.

In summary, persons with transferrin saturation of more than 41%, a level not previously considered to be increased, and who also ingest high amounts of dietary iron have an increased risk for cancer. Having high transferrin saturation with a normal diet did not carry increased risk. The current evidence suggests that if a large proportion of the adult US population ingests high levels of dietary iron, then they have a significantly increased risk for deleterious consequences. Although severe iron deficiency causes serious adverse health effects, these data call into question the strategy of the addition of iron to food by manufacturers. Future research might focus on the benefits of dietary changes in individuals with increased transferrin saturation.

Table 1. Population Characteristics of Adults Aged 25 Years and Older From the NHANES I and NHEFS Studies With Normal (≤ 45%) or Increased (> 45%) Transferrin Saturation (TS) Levels and Low (≤ 18 mg) or High (>18 mg) Iron Uptake Levels

![]()

References

- Mainous AG III, Gill JM, Carek PJ. Elevated serum transferrin saturation and mortality. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:133-138.

- Mainous AG III, Wells B, Carek PJ, Gill JM, Geesey ME. The mortality risk of elevated serum transferrin saturation and consumption of dietary iron. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:139-144.

- Glei M, Latunde-Dada GO, Klinder A, et al. Iron-overload induces oxidative DNA damage in the human colon carcinoma cell line HT29 clone 19A. Mutat Res. 2002;519:151-161.

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1-85.

- Stevens RG, Jones DY, Micozzi MS, Taylor PR. Body iron stores and the risk of cancer. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1047-1052.

- Knekt P, Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Aromaa A, Heliovaara M, Hakulinen T. Body iron stores and risk of cancer. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:379- 382.

- Stevens RG, Graubard BI, Micozzi MS, Neriishi K, Blumberg BS. Moderate elevation of body iron level and increased risk of cancer occurrence and death. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:364-369.

- Gordeuk V, Mukiibi J, Hasstedt SJ, et al. Iron overload in Africa. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:95-100.

- Looker AC, Johnson CL. Prevalence of elevated serum transferrin saturation in adults in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:940- 945.

- Witte DL, Crosby WH, Edwards CQ, Fairbanks VF, Mitros FA. Practice guideline development task force of the College of American Pathologists. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Clin Chim Acta. 1996;245:139- 200.

- Edwards CQ, Kushner JP. Screening for hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1616-1620.

- Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenem, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc: a Report on the Panel of Micronutrients. Standing Committee on the Scientifi c Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2001:290-393.

- Schumann K. Safety aspects of iron in food. Ann Nutr Metab. 2001;45:91-101.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-83.

- Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards model. Biometrika. 1982;69:51-55.

- Fracanzani AL, Conte D, Fraquelli M, et al. Increased cancer risk in a cohort of 230 patients with hereditary hemochromatosis in comparison to matched control patients with non-iron-related chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:647-651.

- Fargion S, Fracanzani AL, Piperno A, et al. Prognostic factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in genetic hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 1994;20:1426-1431.

- Bradbear RA, Bain C, Siskind V, et al. Cohort study of internal malignancy in genetic hemochromatosis and other chronic non-alcoholic liver diseases. JNCI. 1985;75:81-84.

- Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH, Mellemkjar L, Wacholder S, Fraumeni JF. Cancer risk following primary hemochromatosis: a population- based cohort study in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:160-162.

- Adams PC. Population screening for hemochromatosis. Gut. 2000; 46:301-303.

- Smith RA, Glynn TJ. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:453-470.

- Polednak AP. Trends in incidence rates for obesity-associated cancers in the US. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:415-421.

- Jensen OM, Whrendorf J, Rosenquist A, Geser A. The reliability of questionnaire-derived historical dietary information and temporal stability of food habits in individuals. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:281-290.

- James GD, Sealey JE, Alderman MH, Laragh JH. Year to year stability of urine sodium, potassium, aldosterone and PRA in normotensive men and women. Am J Hypertens. 1993;6:86A-90A.

Supported in part by grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration (1D12HP00023-01) and from the Delaware Division of Public Health.

None reported

Arch G. Mainous III, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 295 Calhoun St, Charleston, SC 29425, mainouag@musc.edu

![]()

1 Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC

2 Department of Family and Community Medicine, Christiana Care Health System, Wilmington, Del