What Is the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) in Sleep Apnea Testing?

This Measure Is Commonly Used to Assess Sleep Apnea Severity

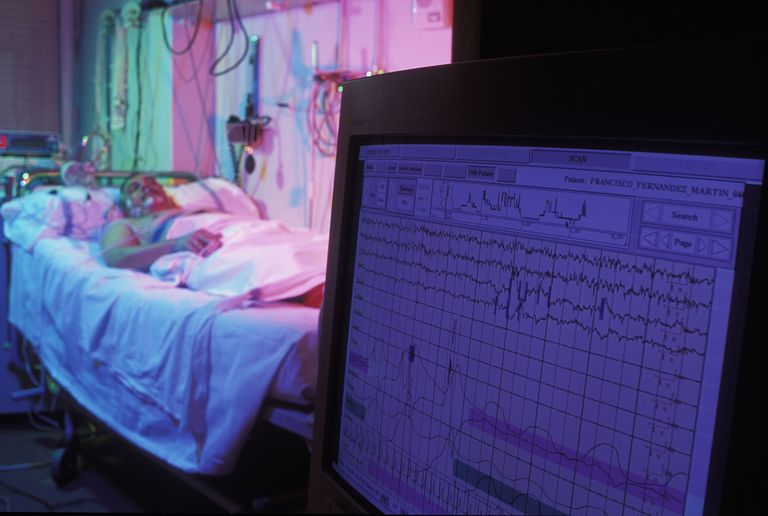

The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is a measure used in sleep apnea studies and CPAP treatment. Credit: Science Picture Co/Collection Mix: Subjects/Getty Images

By Brandon Peters, MD – Reviewed by a board-certified physician.

Updated April 19, 2016

If you have a sleep study such as a polysomnogram or even home sleep testing, you may receive a report from your doctor that describes the severity of your sleep apnea according to the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), but what is the AHI? Learn what the AHI is and how the measure is used to assess the severity of sleep apnea and your response to therapy.

What Is AHI?

AHI, or the apnea-hypopnea index, is a numerical measure that accounts for the number of pauses in your breathing per hour of sleep.

These breathing disturbances are typically associated with either a brief arousal or awakening from sleep or a 3 to 4 percent drop in the blood oxygen levels, called a desaturation. It is used to assess the severity of an individual’s sleep apnea. The AHI overlaps with the respiratory disturbance index (RDI), though the latter differs as it often includes other minor breathing difficulties. The AHI is part of the report from a standard sleep study for sleep apnea.

AHI Measurement During a Sleep Study

A sleep study called a polysomnogram is typically used to diagnose sleep apnea. It is also possible for the condition to be diagnosed based on home testing. A lot of information is collected, and part of the purpose of these studies consists of tracking your breathing patterns through the night. This is accomplished with a sensor that sits in the nostril as well as a respiratory belt that stretches across the chest and often stomach.

In addition, a sensor called an oximeter measures your continuous oxygen and pulse rate by shining a laser light through your fingertip via a clip.

All of this information is analyzed to determine how many times you breathe shallowly or stop breathing altogether during the night. Any partial obstruction of the airway is called a hypopnea.

Hypopnea refers to a transient reduction of airflow (often while asleep) that lasts for at least 10 seconds, shallow breathing or an abnormally low respiratory rate.

A complete cessation in breathing is called apnea. Hypopnea is less severe than apnea (which is a more complete loss of airflow). It may likewise result in a decreased amount of air movement into the lungs and can cause oxygen levels in the blood to drop. It more commonly is due to partial obstruction of the upper airway.

In order to count in the AHI these pauses in breathing must last for 10 seconds and be associated with a decrease in the oxygen levels of the blood or cause an awakening called an arousal. The AHI is the total number of pauses that occur as averaged per hour of sleep.

How AHI Is Used

The AHI is used to classify the severity of your sleep apnea, according to the following criteria for adults:

- Normal: fewer than 5 events per hour of sleep

- Mild: 5-14.9 events per hour of sleep

- Moderate: 15-29.9 events per hour of sleep

- Severe: greater than 30 events per hour of sleep

In children, it is considered abnormal if there is more than one abnormal breathing event per hour of sleep as measured by AHI, and children should never chronically snore.

This classification is useful in determining the best treatment options as well as the likelihood of associated symptoms, including: excessive daytime sleepiness, high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke, and other complications. If the condition is mild or moderate, an oral appliance may be appropriate.

For all levels of severity, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can be considered. Many CPAP machines are able to provide a daily proxy measure of AHI as a way to ensure proper response to therapy.

It is important for your doctor to consider your risk factors for sleep apnea in selecting your treatment. For example, one study estimated that only 30 percent of people with mild obstructive sleep apnea will tolerate CPAP treatment. In addition, you may discover that your AHI is higher when sleeping on your back or during REM sleep, which may have therapeutic implications.

If you have further questions about what your AHI means in your condition, speak with your sleep specialist.

Sources: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. “International classification of sleep disorders: Diagnostic and coding manual.” 2nd ed. 2005. Giles, TL et al. “Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; 3:CD001106.

What Is the Meaning of AHI in Adults?

Apnea-Hypopnea Index Useful to Determine Sleep Apnea Severity

By Brandon Peters, MD – Reviewed by a board-certified physician.

Updated August 04, 2014

If you have had an overnight sleep study called a polysomnogram, your doctor may have provided you with a detailed report, including a measure called the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). What is the meaning of AHI in adults? How does it correspond with the severity of the sleep apnea condition? Learn about the definitions of AHI and what it means for you.

Understanding How AHI is Measured

The AHI is an important calculation made based on the results of a standard overnight sleep study called a polysomnogram.

As part of these tests, there are sensors placed in the nose or near the mouth that measure air movement. There are also belts positioned across the chest and stomach that stretch as breathing occurs. Apnea events occur when the airway becomes completely obstructed and no airflow is detected by the nose and mouth despite effort occurring as measured by the chest and abdominal belts. If the airflow is reduced only partially, but by at least 30 percent as estimated based on a graph of the signal, it is called a hypopnea.

These events are thought to be significant when they occur in the context of two other events: oxygen level drops or arousals from sleep. The oxygenation of the blood is measured with an oximeter, a small sensor that shines a red light through the fingertip. When the oxygen level falls, this is called a desaturation, and drops of at least 3 percent are problematic. Standard sleep studies also record arousals from deep to light sleep and even awakenings with an electroencephalogram (EEG).

These awakenings may fragment sleep, make it unrefreshing, and lead to daytime sleepiness. Apneas and hypopneas are interpreted as disruptive when paired with either oxygen desaturations or arousals.

The AHI is an averaged measure. It is calculated by taking the total number of significant apnea or hypopnea events divided by the total amount of time spent asleep in hours.

In other words, it is the number of times per hour of sleep that the airway partially or completely collapsed, leading to significant drops in the oxygen levels of the blood or arousals from a deeper to a lighter stage of sleep. If your AHI is 15, this means that, on average, 15 times per hour of sleep your breathing was compromised and this led to adverse consequences.

There are some sleep facilities that use other measures to assess this degree of severity. The respiratory-disturbance index (RDI) may be used if a measurement of airway resistance with a pressure esophageal manometer is also included in the study. The oxygen-desaturation index (ODI) attempts to calculate the number of apnea or hypopnea events per hour that lead to an oxygen drop of at least 3 percent. This is thought to be important in assessing the risk of long-term cardiovascular (high blood pressure, heart attack, and heart failure) or neurocognitive (stroke and dementia) consequences. If your sleep study does not contain these more specific measures, this is nothing to worry about.

AHI and the Severity of Sleep Apnea

How does the numeric value as reported by an AHI correlate with the severity of sleep apnea? Although the standards are widely accepted throughout the field of sleep medicine, the cutoffs for each classification are admittedly somewhat arbitrary. Based on research, the following groupings are used:

- Normal range: 0 to 5

- Mild sleep apnea: 5 to 15

- Moderate sleep apnea: 15 to 30

- Severe sleep apnea: 30 and higher

In general, these measures are of added significance if there is evidence of other adverse effects from sleep apnea, including an elevation in the Epworth sleepiness scale above 10, a marker of excessive daytime sleepiness. This information can further be useful as you consider treatment options. For example, mild to moderate sleep apnea may be treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as well as with oral appliances. Positional therapy and other interventions may also be reasonable. Moreover, surgical treatments may be more effective at curing the condition in people with less severe sleep apnea.

There is some controversy regarding people who have a milder degree of sleep apnea. Along this spectrum may be pre-menopausal women (who are protected by the hormones estrogen and progesterone) or people of normal body weight who, rather than having overt sleep apnea, may instead have upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS).

It should additionally be noted that children may have sleep apnea diagnosed at a far lower AHI. Typically, the AHI is thought to be abnormal when it is greater than 1 (though this threshold was previously 2). This is complicated by developmental changes that occur in puberty. Adolescents who have already gone through their major growth spurt may be best assessed using the adult classification. This assessment and determination is best made based on the clinical judgment of your child’s sleep specialist.

If you have further questions about what the AHI means to you, speak with your doctor about the test results and the best treatment options to address your needs.

Source: Kryger, MH et al. “Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine.” Elsevier, 5th edition. 2011.

What Is My Goal AHI with CPAP Treatment for Sleep Apnea Therapy?

Monitoring the AHI Can Guide Therapy, Maximize Benefits

When using CPAP, the goal AHI should resolve sleep apnea. nicolesy/Getty Images

By Brandon Peters, MD – Reviewed by a board-certified physician.

Updated May 07, 2016

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is commonly prescribed to treat sleep apnea. The goal is to improve breathing at night, but how do you know if the CPAP is working? The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) can be a helpful measure to track the effectiveness of your treatment. Learn what your goal AHI should be to maximize the benefits of using CPAP for optimal therapy.

Understanding the Definition of AHI

First, it is important to understand what the AHI actually is.

This measurement is often presented within the context of a sleep study report. It is the number of times per hour of sleep that your airway partially or completely collapses, leading to a brief arousal or a drop in blood oxygen levels. The partial collapse of the airway is called a hypopnea. The complete absence of airflow through the nose and mouth, despite an effort to breathe as measured at the chest and abdomen, is called an apnea event.

The AHI is used to classify the severity of sleep apnea. Fewer than 5 of these breathing events per hour of sleep is considered to be normal in adults. Mild sleep apnea is defined as 5 to 15 events per hour, moderate is 15 to 30 events per hour, and severe is greater than 30 events per hour. Children’s sleep is analyzed with stricter criteria and more than 1 event per hour of sleep is considered to be abnormal.

Using a Goal AHI to Track Treatment Effectiveness

Modern CPAP and bilevel machines are able to track the residual number of breathing events occurring at your current pressure setting.

You may believe that using your CPAP will prevent the condition entirely, but this is not necessarily the case. It depends, in part, on the pressure set by your sleep specialist.

Imagine trying to inflate a long floppy tube by blowing air into it. With too little air, the tube will not open and it will remain collapsed.

Similarly, if the pressure is set too low on your CPAP machine, your upper airway can still collapse. This may result in either persistent hypopnea or apnea events. Moreover, your symptoms may persist because of inadequate treatment.

How a CPAP Machine Tracks Residual Sleep Apnea Events

Newer machines can track your residual abnormal breathing events and generate an AHI. How is this accomplished? Well, the short answer is that these methods are proprietary, confidential, and are not disclosed by the companies who make the devices. In simple terms, however, consider that the machine generates a constant pressure. It can also generate intermittent bursts of additional pressure. It then measures the resistance to this additional pressure. If there is no clear difference in resistance between the lower and higher pressures, it is understood that the airway is open. However, if the airway is still partially (or even completely) collapsing, the additional pressure may encounter resistance. In “auto” machines, this will prompt the machine to turn up the pressure to better support your airway.

Remember that this measurement is not as accurate as that which occurs in a formal sleep study.

The AHI that the machine calculates is then recorded on the compliance data card. Your equipment provider or physician can then download this and generate a report to direct your treatment. It also may be displayed in the morning on the device’s user interface. This information can also be shared to the cloud and provide you information about the effectiveness of your therapy with related programs.

Determining Your Goal AHI to Optimize Therapy

What should your goal AHI be? First, understand that there can be night-to-night variability in this measure. Sleep apnea may be worsened by sleeping more on your back, having more REM sleep, or even by drinking more alcohol near bedtime. Therefore, it is not useful to chase a daily number. Rather, these variations should be averaged out over 30 to 90 days. In general, the AHI should be kept at fewer than 5 events per hour, which is within the normal range. Some sleep specialists will target an AHI of 1 or 2 with the thinking that fewer events will be less disruptive to sleep.

The optimal goal for you may depend on the severity and nature of your initial condition. It may be tempered by your compliance to treatment, with lower pressures allowed to improve comfort. The best pressure setting for you is best determined by your sleep specialist with the average AHI used in the context of your experience with the treatment.

If you have questions about whether your CPAP is working as well as it could be for you, contact your provider to discuss your status and the options available to optimize your therapy. Regular follow-up in clinic will ensure that you treatment is a success.

Why Is There Variability in Sleep Study Results?

Sleep Position, Sleep Stages, Alcohol, and Other Factors May Play a Role

Updated February 09, 2015

If you have had more than one sleep study, with differing results, you might wonder: Why is there variability in sleep study results? Learn about some of the factors that might contribute to these differences and changes over time.

In general, sleep studies are most commonly done to assess for obstructive sleep apnea. One of the most important measurements is the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), which indicates the number of times per hour on average that your airway collapses during sleep, causing either a drop in the oxygen levels of the blood or an awakening from sleep.

This is sometimes reported as the respiratory disturbance index (RDI). These measures are used to determine your severity of sleep apnea, based on the following categories: normal (<5), mild (5-15), moderate (15-30), and severe (>30). These indicators often vary night to night, so why is this?

First, it should be admitted that even if you had 10 nights of sleep studies in a row, you would have 10 different sets of numbers. This is due to factors that may impact sleep apnea that can change quite quickly. For example, sleep position commonly impacts both snoring and sleep apnea. If you spend a night sleeping more on your back, your AHI may worsen as gravity shifts your tongue and blocks the airway more frequently. Spend a little more time on your sides one night and the number may improve.

Another variable is the amount of REM sleep that occurs during a night of sleep. In REM sleep the body’s muscles are relaxed to prevent dream enactment.

During this sleep state, the airway can become more collapsible and worsen sleep apnea. It is normal for the amount of REM to vary somewhat from night to night and this will also affect the average AHI.

There are a few other factors that could vary over the short term. If you drink alcohol, the amount consumed before bedtime may have a role.

Alcohol acts as a muscle relaxant, contributing to airway relaxation and worsening snoring and sleep apnea. If you have nasal congestion from a cold or allergies, this will decrease airflow through the nose, may lead to unstable mouth breathing, and worsen your AHI.

Time can greatly affect your degree of sleep apnea, and comparing studies separated by months or years may identify dramatic changes. Simple aging leads to a loss of muscle tone throughout the body, including along the airway. Women who enter menopause will have more than 10 times the risk of sleep apnea due to hormonal changes. Weight gain in both women and men can crowd the airway and this can worsen sleep apnea, too. In general, a 10% change (up or down) in body weight is likely to impact your degree of sleep apnea.

Other interventions may also affect your sleep study results. For example, if you have undergone surgery to treat sleep apnea, this may affect your condition (hopefully in a favorable way). If you have a test performed with an oral appliance in place, this likewise may change your condition.

These treatments may alter your anatomy and impact the measures used to assess sleep apnea.

Finally, it is important compare apples to apples and oranges to oranges. This means that you should only compare like studies to one another. Formal diagnostic polysomnograms done in a sleep laboratory should not be compared to home sleep tests as the measurements and procedures differ significantly. In addition, testing centers and even sleep professionals may differ somewhat in how strictly they apply the study scoring rules. As a result, the interpretation of the data and the ultimate results may vary slightly.

Sleep study results will be least variable if as many of these conditions can be kept as constant as possible. Many of these subtle variations will not result in a different diagnosis. If you are concerned about the results of your study, or what it might mean for your treatment options, speak with your sleep specialist.

Sources: Kryger, M.H. et al. “Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine.” ExpertConsult, 5th edition, 2011.

What Is Complex or Treatment-Emergent Sleep Apnea?

Causes and Treatments Differ from Obstructive Sleep Apnea

CPAP therapy can sometimes cause complex or treatment-emergent central sleep apnea. Science Picture Co/Getty Images

By Brandon Peters, MD – Reviewed by a board-certified physician.

Sleep apnea can be complex to understand, mostly due to the complicated words that are thrown around. Unfortunately, even some medical providers can misunderstand the meanings of various diagnoses. This can lead to costly and unnecessary testing and treatments. It is very important to understand the symptoms and signs of one diagnosis in particular: complex sleep apnea. What is complex or treatment-emergent sleep apnea?

Learn about this condition, the features and causes, how it is diagnosed, and the most effective treatments (and if treatment is even necessary).

What Is Complex Sleep Apnea?

Complex sleep apnea is also referred to as treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, and this is actually a helpful phrasing of the condition. Complex sleep apnea occurs when someone who previously had obstructive sleep apnea develops central sleep apnea due to the use of treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This is a lot to unpack, so let’s dissect the terms here.

First, obstructive sleep apnea occurs when the upper airway (or throat) collapses during sleep. This can trigger drops in the blood’s oxygen levels as well as arousals or awakenings from sleep. Based on a diagnostic sleep study called a polysomnogram, this condition is present when there are five or more obstructive events occurring per hour of sleep.

These airway collapses may go by various names, including: obstructive apneas, mixed apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory related arousals (RERAs).

Once obstructive sleep apnea is identified, the most common and effective treatment is the use of CPAP therapy. This treatment delivers a constant flow of air through a facial mask.

This additional air keeps the airway from collapsing, or obstructing, and also resolves snoring. In some cases, it may trigger changes in breathing that result in breath holding, a condition called central sleep apnea.

By definition, complex sleep apnea occurs with the use of CPAP treatment. Obstructive events resolve and central apnea events emerge or persist with therapy. These central apnea events must occur at least five times per hour and they should constitute more than 50% of the total number of apnea and hypopnea events. Therefore, if you have a total of 100 apnea events noted while using CPAP therapy, and only 49 (or more likely fewer) are central apnea events, you do not have complex sleep apnea. It is very common for some central apnea events to emerge, but they may not require any additional intervention beyond time.

How Common Is Complex Sleep Apnea?

Complex sleep apnea may be relatively common during the initial treatment period with CPAP or even bilevel therapy. These central apnea events are not better explained by the use of medications (like narcotics or opioid pain medicines) and are not due to heart failure or stroke.

There may be a high number of arousals from sleep and each awakening may be followed by a post-arousal central. These events are more commonly seen in non-REM sleep and may improve slightly in stage 3 or slow-wave sleep.

How common is complex sleep apnea? This is actually a difficult question to answer. The true incidence and degree of persistence is not well defined, due to the fact that it often variably resolves as PAP therapy continues. It is estimated to affect from 2% to 20% of people as they start using CPAP therapy and may be seen more often in the first or second night of use. Therefore, it may be over-identified as part of a titration study in a sleep center. Fortunately, it only persists with therapy in about 2% of people.

What Causes Complex Sleep Apnea?

The exact causes of complex sleep apnea are not fully understood. There may be a number of contributions to the condition, and not all are due to CPAP therapy. Some individuals may be predisposed towards the condition due to instability in their control of breathing. It may occur more commonly among those with difficulty maintaining sleep, such as with insomnia. It seems to be triggered by low carbon dioxide levels in some. If someone has more severe sleep apnea initially (with a higher AHI) or has more central apnea events noted prior to treatment, this may increase the risk. It also seems to occur more in men.

It is interesting to note that other treatments of sleep apnea also seem to increase the risk of developing complex sleep apnea. Surgery and the use of an oral appliance have both been reported to trigger central sleep apnea. It may also occur if the pressures of the PAP therapy are either too high, or conversely too low, as set during a titration study or in subsequent home use.

The Consequences and Treatments of Complex Sleep Apnea

Even though complex sleep apnea generally resolves over time, there are still 2% of people in whom the condition persists and there may be other consequences. Some of these people may require alternative treatments to resolve the disorder.

Complex sleep apnea may be noted to persist on routine download of PAP compliance data. This will usually occur at a routine follow-up appointment with your sleep specialist in the first 3 months of use. If more than five central apnea events are occurring per hour, despite the obstructive sleep apnea events resolving, this might prompt changes. Why might this matter?

Persistent complex sleep apnea associated with a high residual AHI may cause continued sleep fragmentation and oxygen desaturations. This may lead to daytime sleepiness and other long-term health effects. Importantly, this may also compromise PAP therapy: the user may report little benefit and have poor long-term adherence to the treatment.

It is important to recognize that there may be night-to-night variability. In the context of your initial condition, some elevations in the AHI may be tolerated if the overall response to therapy is favorable. Though the devices can provide a rough measure of central apnea events, these are not perfect, and this may be better assessed via a standard polysomnogram.

Resolution of complex sleep apnea may depend on addressing the underlying causes. For example, if the pressures used are simply too high (or, less often, too low), a simple adjustment may resolve the matter. If awakenings are occurring due to mask leak, a proper fitting may help. In some cases, it may be necessary to switch to bilevel ST (with a timed breath rate that can be delivered during breath pauses) or ASV therapy. These therapy modalities will often require a titration study to find the optimal device settings.

The most prudent treatment is often the most effective: time. Complex sleep apnea will usually improve in 98% of cases as therapy continues. It may not require any further intervention beyond waiting and watching the remaining events resolve on their own.

Sources:

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014.

Javajeri S, Smith J, Chung E. “The prevalence and natural history of complex sleep apnea.” J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:205-211.

Lehman S et al. “Central sleep apnea on commencement of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with a primary diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea.” J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:462-466.

Westhoff M, Arzt M, Litterst P. “Prevalence and treatment of central sleep apnea emerging after initiation of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea without evidence of heart failure.” Sleep Breath 2012;16:71-8.